Who are

isolated

indigenous

peoples?

Isolated indigenous peoples are those who choose to live in a way that makes direct contact, close dialogue, meetings, assemblies or hearings impossible. They live physically apart from other collectives, which does not necessarily mean that there is an absence of relationships. They often make unequivocal announcements that they reject contact. They purposely leave traces, coverings and traps, explicit messages of denial to the invasion and destruction of their territories. The very decision to flee and reject forced contact is a clear expression of this will. In the National Foundation for Indigenous Peoples' public policy they are referred to by the acronym PIIRC (Isolated and Recently Contacted Indigenous Peoples).

In Brazil, the state recognises the existence of 114 records of the presence of these peoples, of which 28 have had their existence officially confirmed, following a process of localization that has to be carried out by specialised technicians. Therefore, 86 officially recognised records still need to be analysed and remain "unconfirmed", which raises the level of vulnerability of these groups. It is important to remember that many leaders, peoples and their organisations point to this presence beyond the official data recorded, systematised and presented by FUNAI. For this reason, the number of isolated groups may be significantly higher than what is officially registered.

There are 114 records

of isolated peoples

in Brazil, the highest

concentration in the world.

There are at least 20 indigenous lands (ILs) with officially confirmed presence of these peoples, representing 23% of the total surface area of ILs in the country. The ten most deforested Indigenous Lands between 2008 and 2021 have records of presence of isolated peoples in seven of them. There are more than a dozen Indigenous Lands whose demarcation processes are pending or paralysed. There are at least 40 records of presence of isolated indigenous people outside the protection of Indigenous Lands, approximately 15 of which are in regions with high rates of deforestation. Let's be clear, the phenomenon of "isolation" is no exception, it's more common than you might think.

Since 1987, the Brazilian state has had a specific public policy for these peoples, based on respecting their condition of "isolation", considering this position to be the maximum expression of their will. It is a right recognised by the 1988 Federal Constitution.

Isolated peoples

on the international

arena

According to the United Nations and the Inter-American Commission on Human Rights, isolated peoples are peoples or segments of indigenous peoples who do not maintain regular contact with the majority population and who also tend to avoid all contact with people outside their group.

Notwithstanding the established concept of "isolated", there is a great diversity of contexts of "isolation", from small groups who have survived successive massacres and who therefore avoid contact with other people at all costs, to demographically significant peoples who establish intermittent and long-distance relations with other neighbouring peoples, whether through war relations, looting or purposefully produced traces, as well as other forms of interaction.

In South

America, 185 records

Fonte: GTI-Piaci

The phenomenon of "isolation" occurs above all in the Amazon region, in regions that are difficult to access due to their geographical and environmental characteristics and the historical process of colonisation. The presence of these groups is also recorded in the Brazilian Cerrado and in the Gran Chaco region between Paraguay and Bolivia.

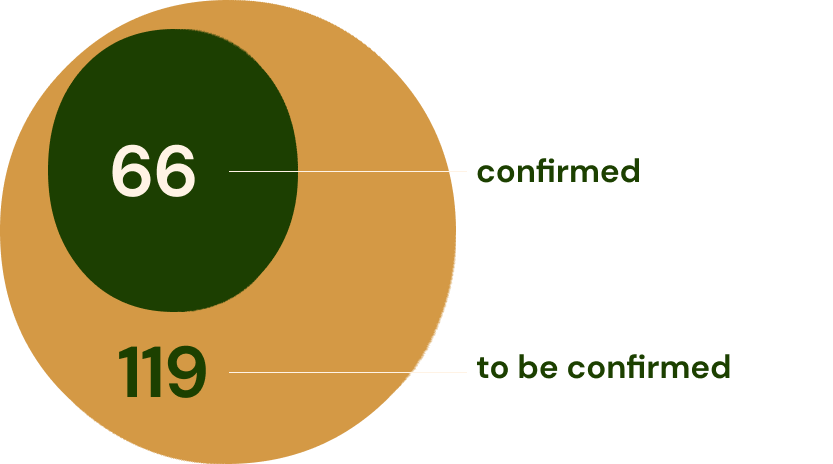

In all, there are 185 records of the presence of peoples in isolation in South America. Of these, 66 have been confirmed and 119 have yet to be confirmed.

In general, peoples in situations of isolation are subject to specific contexts of vulnerability, such as the socio-epidemiological one, due to their lack of immunological memory for certain diseases. What for us is a simple flu, for them can lead to serious illness and death.

It is essential that our society realises that isolated peoples opt for this way of life, based either on traumatic contact experiences that took place in the past, or on other internal decision-making processes that aim, above all, to reduce their degree of vulnerability in relation to contact and interaction with the society that surrounds them.

Currently, existing national and international guidelines and legal frameworks guarantee and protect the decision of isolated peoples to remain so. To this end, it is important to guarantee exclusive use of their territories. Isolated peoples depend exclusively on hunting, fishing and gathering in their territories. Therefore, any action that negatively impacts the environmental conditions of these territories puts them at real risk of genocide.

It is important to realise that these peoples are our contemporaries, subject to the same ecological and historical processes that afflict us and of which we are a part. What differentiates them from other indigenous peoples, in general, is the greater selectivity and control of the interactions they establish with other people.

Indigenous

peoples isolated

in Brazil: where are they?

- Records of Uncontacted Peoples

- Indigenous lands with registration of Isolated Peoples

- Indigenous lands without registration of Isolated Peoples

In Acre, the Envira Ethno-Environmental Protection Front (FPEE) of the National Foundation for Indigenous Peoples (FUNAI) officially works with eight references of isolated indigenous people in the state, six of which are "confirmed" and two of which are under "study". Three of them refer to isolated Mashco-Piro groups, who occupy an extensive area of river headwaters in the Brazil-Peru border region. The records of isolated peoples in Acre are located in the IL Mamoadate, IL Kampa and Isolados do Rio Envira, IL Riozinho do Alto Envira, IL Jaminawa-Envira, IL Kaxinawá do Rio Humaitá, TI Kulina do Rio Envira, TI Kaxinawá/Ashaninka do Rio Breu, IL Alto Tarauacá (exclusively for isolated peoples) and IL Igarapé Taboca Alto Tarauacá (in a Restricted Use situation). There are also records in the Chandless State Park, the Rio Acre Ecological Station and the Serra do Divisor National Park.

The state of Amazonas has the largest number of records of presence of isolated indigenous peoples. There is evidence of their existence in practically every region of the state. The Vale do Javari Indigenous Land, located on the border with Peru, is where we find the largest known group of these peoples in the country. The state of Acre also has a large presence of isolated indigenous peoples. The corridor formed by Acre and the departments of Ucayali, Madre Dios and Cuzco, in Peru, is a territory occupied by an immense diversity of isolated or recently contacted (or initial contact) peoples.

In Roraima there are isolated peoples in the Yanomami Indigenous Land, on the border with Venezuela, and in the Waimiri Atroari Indigenous Land. Specifically with regard to the isolated indigenous people with a confirmed presence in the Yanomami Indigenous Land, it should be emphasised that their territory has been gravely invaded and depleted by mining activities, and is therefore in a situation of extreme vulnerability.

In the state of Rondônia there are emblematic cases of violations of indigenous rights, such as the case of the Akuntsu and Kanoê in the Omerê Indigenous Land; and the recently deceased "Indio do Buraco" in the Tanaru Indigenous Land. These peoples were decimated in successive massacres during the implementation of colonisation and economic development projects in Rondônia between the 1970s and 1990s. It was also in Rondônia that the first indigenous land for the exclusive use of an isolated indigenous people was demarcated in the early 1990s: the Massaco Indigenous Land. There is also the Uru Eu Wau Wau Indigenous Land where, in addition to the Amondawa, Jupaú and Oro Win peoples, there are at least two isolated indigenous peoples. Since the demarcation process began at the end of the 1980s, this indigenous land has been under intense pressure and large areas have been invaded by land grabbers, which is why it has had high rates of deforestation. For this reason, the process of clearing invaded areas in the Uru Eu Wau Wau Indigenous Land has been for years.

The western region of Maranhão state is traditional Awá territory. Between the 1970s and 1990s, several small groups were contacted in the context of the advance of colonisation in the region and the construction of the Carajás railway. The state recognises the presence of isolated groups in the region, located in the Caru and Araribóia Indigenous Lands. There is also the possibility of an isolated remnant group in the Awá Indigenous Land and the Gurupi Biological Reserve.

In Pará there is also a large amount of information pointing to the presence of isolated peoples, from the north, on the border with the two Guyanas, Suriname and the state of Amapá, to the central region of the state, in the middle Xingu River region - including in the context of the Belo Monte Hydroelectric Power Plant, where the Ituna-Itatá Indigenous Land is located, protected by a Restriction of Use ordinance. The possible presence of isolated indigenous people is also recorded in the south of Pará, in the upper Xingu river basin - in the Kayapó, Menkragnoti Indigenous Lands; and in the middle and upper Tapajós river regions.

In the north-west of Mato Grosso the existence of at least two isolated peoples has been confirmed, both of Tupi-Kawahiva linguistic affiliation, survivors of massacres. They have historically lived trapped in their own territory, in a constant process of flight due to the invasion of loggers and land grabbers for cattle ranches, in the Kawahiva do Rio Pardo and Piripkura Indigenous Lands. In addition to these two confirmed groups, there are a number of recurring indications of the probable presence of other isolated indigenous peoples, such as in the Apiaká do Pontal e Isolados Indigenous Land. In Tocantins, reports of the presence of isolated Avá groups in the region encompassed by Ilha do Bananal and surroundings have been repeated historically, especially in the Inãwébohona Indigenous Land.

In the state of Goiás , the history of massacres, flight and resistance of the Avá Canoeiro people is well known. There are also reports of the presence of groups that are still isolated in the Chapada dos Veadeiros macro-region, specifically in the municipality of Cavalcante.

In Acre, the Envira Ethno-Environmental Protection Front (FPEE) of the National Foundation for Indigenous Peoples (FUNAI) officially works with eight references of isolated indigenous people in the state, six of which are "confirmed" and two of which are under "study". Three of them refer to isolated Mashco-Piro groups, who occupy an extensive area of river headwaters in the Brazil-Peru border region. The records of isolated peoples in Acre are located in the IL Mamoadate, IL Kampa and Isolados do Rio Envira, IL Riozinho do Alto Envira, IL Jaminawa-Envira, IL Kaxinawá do Rio Humaitá, TI Kulina do Rio Envira, TI Kaxinawá/Ashaninka do Rio Breu, IL Alto Tarauacá (exclusively for isolated peoples) and IL Igarapé Taboca Alto Tarauacá (in a Restricted Use situation). There are also records in the Chandless State Park, the Rio Acre Ecological Station and the Serra do Divisor National Park.

The state of Amazonas has the largest number of records of presence of isolated indigenous peoples. There is evidence of their existence in practically every region of the state. The Vale do Javari Indigenous Land, located on the border with Peru, is where we find the largest known group of these peoples in the country. The state of Acre also has a large presence of isolated indigenous peoples. The corridor formed by Acre and the departments of Ucayali, Madre Dios and Cuzco, in Peru, is a territory occupied by an immense diversity of isolated or recently contacted (or initial contact) peoples.

In Roraima there are isolated peoples in the Yanomami Indigenous Land, on the border with Venezuela, and in the Waimiri Atroari Indigenous Land. Specifically with regard to the isolated indigenous people with a confirmed presence in the Yanomami Indigenous Land, it should be emphasised that their territory has been gravely invaded and depleted by mining activities, and is therefore in a situation of extreme vulnerability.

In the state of Rondônia there are emblematic cases of violations of indigenous rights, such as the case of the Akuntsu and Kanoê in the Omerê Indigenous Land; and the recently deceased "Indio do Buraco" in the Tanaru Indigenous Land. These peoples were decimated in successive massacres during the implementation of colonisation and economic development projects in Rondônia between the 1970s and 1990s. It was also in Rondônia that the first indigenous land for the exclusive use of an isolated indigenous people was demarcated in the early 1990s: the Massaco Indigenous Land. There is also the Uru Eu Wau Wau Indigenous Land where, in addition to the Amondawa, Jupaú and Oro Win peoples, there are at least two isolated indigenous peoples. Since the demarcation process began at the end of the 1980s, this indigenous land has been under intense pressure and large areas have been invaded by land grabbers, which is why it has had high rates of deforestation. For this reason, the process of clearing invaded areas in the Uru Eu Wau Wau Indigenous Land has been for years.

The western region of Maranhão state is traditional Awá territory. Between the 1970s and 1990s, several small groups were contacted in the context of the advance of colonisation in the region and the construction of the Carajás railway. The state recognises the presence of isolated groups in the region, located in the Caru and Araribóia Indigenous Lands. There is also the possibility of an isolated remnant group in the Awá Indigenous Land and the Gurupi Biological Reserve.

In Pará there is also a large amount of information pointing to the presence of isolated peoples, from the north, on the border with the two Guyanas, Suriname and the state of Amapá, to the central region of the state, in the middle Xingu River region - including in the context of the Belo Monte Hydroelectric Power Plant, where the Ituna-Itatá Indigenous Land is located, protected by a Restriction of Use ordinance. The possible presence of isolated indigenous people is also recorded in the south of Pará, in the upper Xingu river basin - in the Kayapó, Menkragnoti Indigenous Lands; and in the middle and upper Tapajós river regions.

In the north-west of Mato Grosso the existence of at least two isolated peoples has been confirmed, both of Tupi-Kawahiva linguistic affiliation, survivors of massacres. They have historically lived trapped in their own territory, in a constant process of flight due to the invasion of loggers and land grabbers for cattle ranches, in the Kawahiva do Rio Pardo and Piripkura Indigenous Lands. In addition to these two confirmed groups, there are a number of recurring indications of the probable presence of other isolated indigenous peoples, such as in the Apiaká do Pontal e Isolados Indigenous Land. In Tocantins, reports of the presence of isolated Avá groups in the region encompassed by Ilha do Bananal and surroundings have been repeated historically, especially in the Inãwébohona Indigenous Land. In the state of Goiás , the history of massacres, flight and resistance of the Avá Canoeiro people is well known. There are also reports of the presence of groups that are still isolated in the Chapada dos Veadeiros macro-region, specifically in the municipality of Cavalcante.

Redemocratisation

and the self-determination

of indigenous peoples

Throughout the 20th century (and, of course, in previous centuries), especially during the period of the military dictatorship (1964-1985), the advance of major infrastructure and economic expansion projects, especially in the Amazon region, forced several previously isolated indigenous peoples into contact with colonisation fronts, causing major population losses and sometimes even the genocide of entire groups as a result, mostly due to epidemic outbreaks contracted after the first contacts.

In the 1980s, the country's re-democratisation process was accompanied by a strong mobilisation of civil society organisations. Brazilian society finally won the right to vote in the 1989 elections. Before that, in 1988, Brazil promulgated its new constitution - the Citizen Constitution - which set new standards for the relationship between the state and Brazilian society in relation to indigenous peoples, recognising their self-determination, their territorial rights, their "uses, customs and traditions", emancipating them from the practice of tutelage and overcoming the state's policy of "integrating" these populations.

Legal milestones

for indigenous

peoples' right to

self-determination:

1988

Federal

Constitution

(Brazil)

1989

ILO

Convention

169 (World)

In the same context, globally, in 1989, the International Labour Organisation (ILO) - an agency within the intricate structure of the United Nations (UN) - adopted Convention 169 which, by replacing the old Convention 107 of 1957, in short, abandoned the idea of "integration" once and for all, consolidated and paved the way for the recognition of the self-determination of indigenous peoples along international lines. The same Convention is known for indicating the right of indigenous peoples to free, prior and informed consultation on any and all measures adopted by the States which affect them. Later, at the 1992 United Nations Conference on Environment and Development in Rio de Janeiro, the Earth Summit, the recognition of the contribution of indigenous peoples to the maintenance of biodiversity as well as the conception of "precaution" as a primary guideline for the conservation of ecosystems - or the Precautionary Principle - began to take shape in international discussions and, at State level, in general, in the implementation of public policies. The precautionary principle is undoubtedly one of the main foundations of PIIRC rights.

The mobilisation

of civil

society and the

"no contact” policy

It is in this atmosphere of effervescence that the "no-contact" policy was created in Brazil. From the creation of the Indian Protection Service in 1910 (the inaugural milestone of contemporary indigenist policy) until 1987 – the year of turning point for the "no-contact" policy - State practices were based on attracting and contacting isolated indigenous peoples as a central guideline for the protection of these populations. This occurred more intensely in the context of the expansion of economic fronts. The practice of forced contact proved to be extremely violent for the lives of indigenous peoples, a fact that is widely known.

Civil society organisations and indigenous peoples had already been discussing and criticising the practices of forced contact carried out by the State via FUNAI and missionaries. Indigenists who would go on to found the Kanindé Ethno-Environmental Defence Association in 1992, together with indigenous peoples in Rondônia, were pressing for no contact to be made with isolated indigenous people in the state, like those who lived in the Guaporé Biological Reserve between the late 1980s and early 1990s. In 1986, the Indigenous Missionary Council (CIMI) and Operation Anchieta (OPAN) organised a meeting to discuss , specifically, the living conditions of isolated indigenous peoples amidst the advance of economic expansion fronts in the Amazon region and, at the same time, made harsh criticism to the processes of forced contact.

The "no-contact"

paradigm for

isolated indigenous

peoples began in

1987

1988

There were other field experiences that unfolded into discussions about the possibility of "no-contact" as a protection measure before 1987. Between 1984 and 1985, when anthropologists were mediating tensions between ranchers and an isolated Avá Canoeiro group, in northern Goiás state, during the attraction and contact processes being carried out by FUNAI. At the time, the possibility of not making contact with the small and elusive Avá Canoeiro group, which was the goal of the official indigenist agency, was raised. These and other cases occurred and were, to a large extent, also responsible for the drastic shift in paradigm in 1987.

The "no-contact" paradigm officially incorporated into the indigenist policy for isolated indigenous peoples (PII) began in 1987 and 1988, following a meeting between FUNAI and indigenous experts and anthropologists. The understandings and consensus established at the meeting were published by FUNAI (between 1987 and 1988) through ordinances that formalised and guided the new institutional stance of "no-contact": the "System for the Protection of Isolated Indians" (SPII) was standardised, a specific sector was created within FUNAI to work exclusively on the issue (the Coordination of Isolated Indians); and basic lines of work were established, such as the "no-contact" guideline itself.

The isolation of indigenous peoples is not only the result of forced displacement and, therefore, processes of resistance, but also a clear indication of Amerindian 'discontinuity' caused by the violence of the colonial project. The Amerindian genocide would see in the 'isolation', so to speak, one of its obvious expressions, whose forests, territories and bodies are intertwined in the same historical process of violence.⁴Ver Ribeiro et al, 2022., um indício claro de descontinuidades ameríndias provocadas pela violência do projeto colonial. O genocídio ameríndio teria no isolamento, por assim dizer, uma de suas evidentes expressões, cujas florestas, territórios e corpos estão entrelaçados em um mesmo processo histórico de violência⁵ Ver Amorim, 2022, p. 215..

On aspects

of vulnerability

Isolated indigenous peoples and those considered to be recently contacted are subject to a large number of areas of vulnerability, largely caused by the State itself. Furthermore, the consequences of this enormous pressure tend to have a greater impact on their collectives.

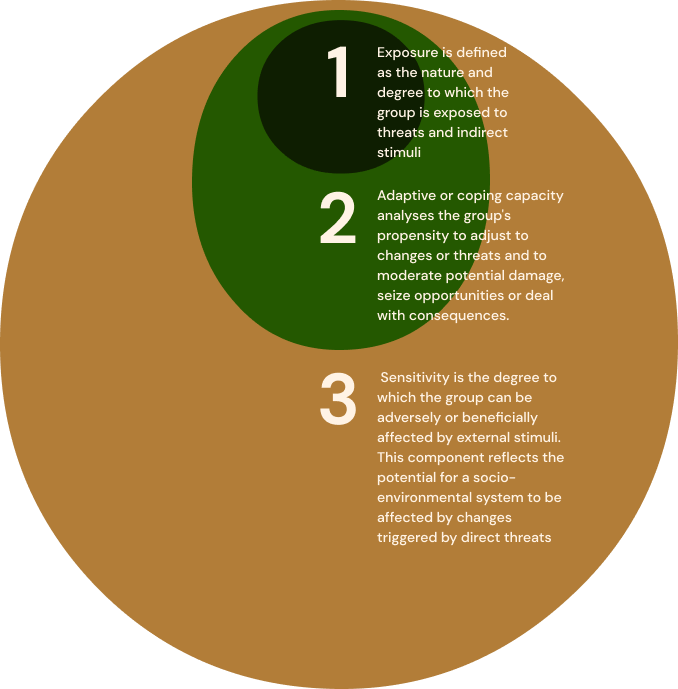

The mechanisms that produce situations of vulnerability generally consist of at least three components which, in correlation, modulate the negative consequences caused by pressures on indigenous peoples:

The fact is that from the perspective of defining criteria for planning and directing public policies, the aspects that result in vulnerability are still little studied and analysed. It is very common in the processes of planning, implementing and evaluating public policies for indigenous peoples for them to be blamed for their own vulnerability. Isolated peoples are not vulnerable, they are subject to contexts of vulnerability. In any case, it is possible to systematise some of the vulnerabilities to which these isolated and recently contacted indigenous peoples are subject from different vectors and perspectives;

1

epidemiological vulnerability, due to the lack of immunological memory in their bodies to defend against certain diseases;

2

demographic vulnerability due to the fragility of their population, mainly as a result of the high mortality rates resulting from contact;

3

territorial vulnerability, due to the continuous pressure on their territories, the failure to recognise their territorial rights (notably the demarcation of indigenous lands), given the close connection between these peoples and their territories;

4

political vulnerability, due to the inability of these peoples to manifest themselves through the mechanisms of representation commonly accepted by the State, such as associations or assemblies, for example;

5

socio-cultural vulnerability, which stems from the death of those most vulnerable to epidemics, such as children and the elderly. With their death, the group loses political leaders, counsellors and spiritual guides, and with their death, the ability to renew society is compromised in the medium term, and may even change cultural standards for the formation of couples;

6

legal vulnerability, which is constituted, on one hand, by the lack of specific legislation to deal with the issue and, on the other, by the lack of knowledge that legal operators, lawyers, prosecutors, judges and other legal actors have about the rights and specificities of the PIIRC.

Violence

and genocide

There are countless cases of violence against isolated peoples and their forests during Brazil's dictatorships which have been little studied, systematised and exposed. We have, for example, the cases of the isolated peoples in the Vale do Javari Indigenous Land, who suffered successive acts of violence during the military dictatorship. In Maranhão, there are cases in various local Awá groups, some were massacred, others "rescued" by FUNAI during the construction of the Carajás Railway and the BR-222 motorway. Incredibly, some segments remain in isolation in the forests still standing in the region. In Rondônia, there are cases of recently contacted Akuntsu and Kanoê peoples, and the peoples who still live in isolation in the Uru Eu Wau Wau Indigenous Land, torn apart by State colonisation projects financed by the World Bank (Polonoroeste). There are countless other cases yet to be revealed.

The case of the "Indian of the hole" is emblematic. Although this individual was first located by FUNAI in the mid-1990s, there is a possibility that (at least part of) the massacres suffered by his people took place in the 1980s or even earlier, also as a result of State development and colonisation projects. Similar genocidal practices occurred against the Piripkura and Kawahiva do Rio Pardo peoples, in Mato Grosso state , aggravated by the construction of the MT-206 motorway in the mid-80s. All these cases, and others, urgently need investigation, memory, truth and justice.

The concept of "isolation" is closely linked to the enormous challenge of proving the existence of these peoples and, consequently, officially recognising them as subjects of rights. It is precisely because of this peculiarity, the tendency towards legal invisibility, that the States must adopt more specific measures.

There are difficulties and (culpable) omissions by the State in preventing, avoiding or responding to violence against these peoples. Before proving violence, we have to prove that they exist.⁶Ver Palmquist, 2018.For rights to be effective, the existence of isolated peoples must first be proven, persuaded, widely and locally recognised. Otherwise, their vulnerability increases considerably. Without this recognition, any kind of violence against them is legitimised, because for the State and its detractors, they don't exist.⁷Ver Amorim, 2018..

Isolated peoples exist as subjects of rights when their existence is documented and systematised. For this reason, documentary and audiovisual collections must be compiled which, in themselves, can break through the barrier of invisibility imposed by the status quo. It is essential that strategies are built to organise and safeguard these collections. Where possible, the Peoples involved should have access to these collections.

Consultation

and consent

for Isolated

Indigenous

Peoples

In the case of isolated peoples, the choice of isolation is an express manifestation of their political decision for autonomy. The traces they leave behind, such as traps, coverings and encampments, among others, are evidence of this manifestation. Attitudes of flight and rejection of contact attempts are, in themselves, clear manifestations of will. According to the 1988 Constitution, which guarantees the autonomy of indigenous peoples, and international regulations, the expression of will through isolation should be understood as a non-consent to forced contact and activities to exploit and destroy their territories.

Traces such as

traps, coverings,

tapiris,

among others,

are evidence of the

Manifestation of isolation.

Furthermore, the application of the right to consultation and consent is closely related to the processes of official recognition of presence. For this reason, actions to recognise the presence of isolated indigenous peoples, such as the research processes and localization expeditions carried out by FUNAI, should be considered, in the case of isolated peoples, as part of what would be the protocols for applying the right to consultation or free, prior and informed consent, in accordance with ILO Convention 169. It is important to remember that the State in no way represents the will of these peoples in the context of implementing measures that affect them or, for example, in environmental licensing processes.

Representation occurs through their clear manifestations of rejection and non-consent. Therefore, any forced contact initiative should be considered a violation of the fundamental rights of isolated indigenous peoples, with the exception of cases in which situations of extreme risk and vulnerability are verified, or in cases in which the will for definitive and sustained approaches(contact) are clearly demonstrated. Therefore, forced attempts at contact must be held accountable and punished.

Sign up to receive our newsletter.