Delays in their eviction, ordered by the Supreme Court as a result of ADPF 709, benefit invaders

On 29 January, chief André Karipuna, leader of the Karipuna Indigenous Land in Rondônia, denounced the existence of a deforested area in the south where the indigenous people noticed theft of timber, movement of trucks and the planting of grass for cattle raising – all indications of an attempt at land grabbing by the invaders. The invaded area is the same where sightings of isolated indigenous people, who have not yet been identified by the Brazilian state, have been reported.

In addition, cattle have recently been introduced and there are new areas of deforestation, with the daily presence of invaders growing crops, setting the precedent for other initiatives with impunity. The situation means that the residents are afraid to move freely on their land, since the invaders move around in groups and are possibly armed.

The presence of isolated indigenous people in Karipuna land has been historically recorded in the south, which has been greatly affected by invasions. Possibly because of the invasions in the south, signs of the presence of isolated indigenous people are beginning to appear in the northern part of the territory, getting closer to the village of Panorama, where the Karipuna live.

The Karipuna people, who speak the Tupi-Kawahiva language, were victims of a tragic reduction in their population caused by the colonial invasion, with just 14 survivors in 2004. Today there are 62 people, a small number to monitor the whole land. Invasions of the Karipuna Indigenous Land occur regularly, so operations to remove invaders are constantly needed. Chief André Karipuna emphasises that his people have been continuously denouncing invasions for eight years. In 2018, Adriano Karipuna, a spokesperson for the Karipuna, denounced their situation to the United Nations Human Rights Council. Worried about the persistence of the situation, he emphasises that "When the Marco Temporal* was just a bill, they [the invaders] were already entering without fear. Now that it's been approved, they're reopening previously invaded areas and adding cattle. Even government agents, such as indigenous health workers, are afraid of going into our land and being ambushed ”.

The alarming situation led the Karipuna Indigenous Territory to be included in the government's plan for removal of invaders, within the scope of the Claim of Non-Compliance with Fundamental Precept (ADPF) 709, by order of Supreme Court Judge Luís Roberto Barroso. The court orders included in Public Civil Actions Nºs. 10006683-89.2020.4.01.4100 and 1000723-26.2018.4.01.4100 (MPF/RO) are for the Armed Forces, the Environmental Military Police, the Military Police, inspectors from the State Secretariat for Environmental Development, and IBAMA (Brazilian Environment Agency) and FUNAI agents to act in compliance with this decision. In May 2023, the Federal Police raided 12 of the Indigenous Land's main deforestation hotspots and 20 logging companies in the surrounding area. The one-off action, however, is insufficient considering the territory's security needs.

The Karipuna Indigenous Land stretches over three municipalities: the capital, Porto Velho, Nova Mamoré, which borders Bolivia, and Buritis. In all three municipalities there are logging companies and sawmills in full swing, claims Adriano Karipuna: "I've flown over the region and noticed that there are no forested areas left in private areas, only in the Indigenous Land. But it's crying out for help”. In the 2023 operation, inspectors seized 7,400 cubic metres of timber because they showed discrepancies between the species impounded and those declared to the Forest Origin Document Control System (Sisdof). The difficulty in tracing illegally extracted timber is a cause of great concern. According to the Karipuna leader, the product's destination should be looked into: "we imagine that people with high acquisiton and political power are in charge, because nobody is punished and the invasions continue, often taking advantage of rural producers associations, using them laranjas*".

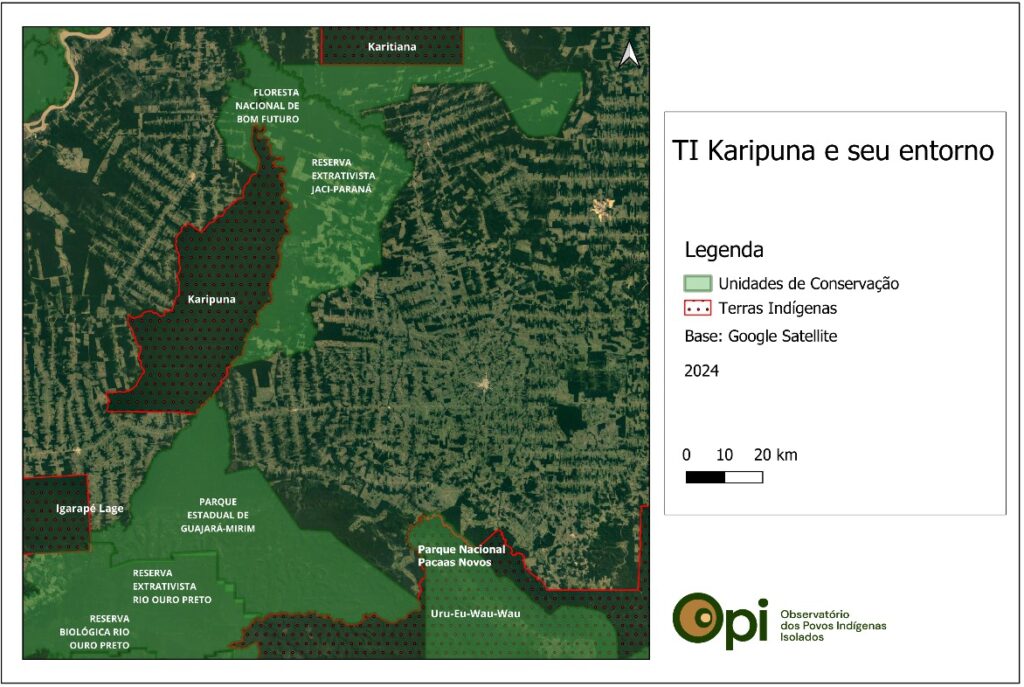

The Karipuna land is located in an area of Rondônia state with ideal characteristics for the creation of a socio-environmental protection corridor, connecting the Karitiana Indigenous Land in the north, the Bom Futuro National Forest, the Jaci-Paraná Extractive Reserve and the Uru Eu Wau Wau Indigenous Land in the south, passing through the Guajará Mirim State Park. A rare opportunity for conservation in the most deforested state in the Amazon region.

If the defence of these territories were successful, the area of continuous forest would help safeguard the isolated indigenous peoples whose existence has yet to be confirmed by the state: recorded in the Bom Futuro Flona and in the northern part of the Uru Eu Wau Wau Indigenous Land, as well as the possible presence of isolated peoples inside the Karipuna Indigenous Land.

Delay and violations

Despite being included among the Indigenous Lands benefiting from an invaders' removal plan in ADPF 709, so far the process has been slow and insufficient. The leaders report difficulty in talking to appropriate bodies in order to understand what actions are being planned. The leaders put themselves in danger by denouncing the situation and have already suffered threats and ambush attempts without so far achieving any concrete results. The indigenous people demand that their land should be permanently monitored by river and land.

In addition to the removal of invaders, the leaders are asking for reparations to keep the land free of invaders and mitigate the damage caused so far, such as replanting of degraded areas, continuous surveillance and psychological care for the residents, who report serious emotional consequences from the situation of insecurity.

Another form of violence experienced by the Karipuna has resulted from the damming of the surrounding rivers by large hydroelectric power plants. After a major flood of their land in 2023, the indigenous people received support to rebuild their homes in a safer area, but they are demanding assistance for the installation of a water supply system:

In March last year, the village of Panorama, in the Karipuna Indigenous Land, was flooded by rain and the increase in the level of the reservoir of the Madeira River Hydroelectric Complex, leaving all the houses underwater with damaged structures. As a result, the village had to be relocated to higher ground. In a letter, the Karipuna people describe the situation:

"With the help of the German Embassy and the Indigenous Missionary Council (CIMI), 12 new houses have been built in a safe place, but they need to have the water supply to the houses, for their bathrooms and service areas, where pipes have already been installed. To do this, the Indigenous Health Districts (DSEI) needs to extend the water distribution network to all the families, because at the moment there is only one water tank, in the old part of the village, which won't meet the needs of the 12 families," says the letter. Several documents have been sent to the DSEI and the Public Prosecutor's Office (MPF), but so far there is no indication that a water supply will be guaranteed for the families who have been forced to move.

Fearing the continuation and repetition of the environmental violence they are already suffering, they have also denounced recent studies for the construction of a binational hydroelectric power plant between Brazil and Bolivia in the Madeira river basin. The proposal is for the construction of two dams, and the hydroelectric plant would be installed at the junction of the Ribeirão igarapé* with the Madeira river, in Nova Mamoré (RO) and Nueva Esperanza (Bolivia), producing more energy than the Santo Antônio and Jirau dams, affecting a large indigenous and extractivist population around it. In addition to this major project, studies are already being carried out for the implementation of the Tabajara hydroelectric plant, on the Machado River. With these denunciations, the Karipuna leaders concerns reach beyond their own land: "The feeling is that we indigenous peoples are surrounded," says Adriano Karipuna, "I'm worried about the entire population that could be affected, like us."